Acceleration of ML classifiers

Our previous experience shows that using machine learning (ML) techniques can achieve high accuracy in classifying application protocols within encrypted traffic 1. Various ML models were tested, including neural networks and decision trees, with both types achieving comparable results in terms of accuracy. In addition, decision trees allow for the analysis and interpretation of model behavior. Among the techniques investigated, such as Random Forest and Gradient Boosting, the Gradient Boosting method proved to be more powerful, which led to the use of the LightGBM library 2 for building the resulting models.

A number of models have been created for classifying encrypted traffic, from simple ones that identify specific application protocols to complex models capable of classifying hundreds of protocols simultaneously. For example, a model for classifying QUIC protocol traffic identifies up to 101 different applications 1, while a model for TLS traffic detects up to 186 different application protocols 3.

Currently, these models are implemented at the software level and achieve performance in the order of units to tens of thousands of classifications per second, which is sufficient for traffic analysis on a monitoring probe with a link speed of 100Gb/s. However, in cases with multiple lines or when aggregating traffic from multiple probes, the software implementation is insufficient.

As part of the project, we therefore investigated the possibilities of hardware acceleration of encrypted traffic classification, focused on decision trees and created software that automatically converts existing LightGBM models to their circuit implementation in the VHDL language.

Decision Trees and Gradient Boosting

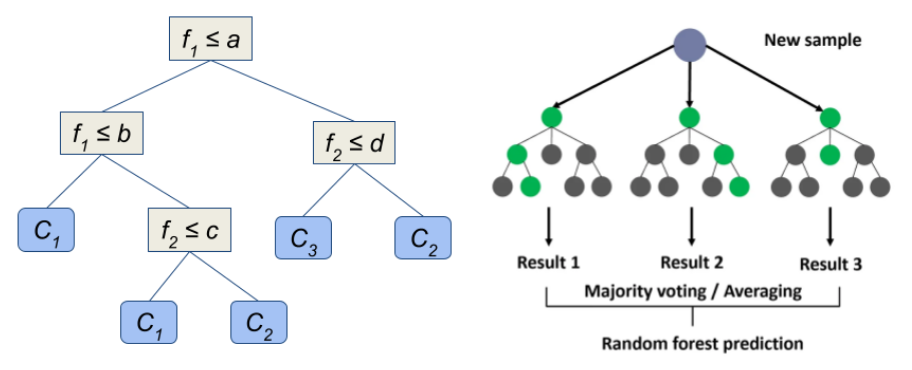

A decision tree is a basic data structure for classification, where the input is a vector of object features (e.g., network flow) and the output is the identification of the class to which the object belongs. The tree structure compares the input features with predefined thresholds and, based on the results, processing continues in the left or right subtree until a leaf node containing information about the class is reached (see Figure 1, left).

Figure 1: Decision tree (general), processing method using the Random Forest technique.

Figure 1: Decision tree (general), processing method using the Random Forest technique.

Decision trees themselves are not robust enough, so more complex models such as Random Forest (RF) are used, which combines the results of many trees (see Figure 1, right). An alternative is Gradient Boosting (GB), which gradually refines the result of the previous model in iterations (see Figure 2, right). Each tree in the GB contributes a decimal number representing the degree of belonging of the object to the class (log-odds ratio), and these values are summed and converted to probabilities. The number of trees is equal to the number of iterations multiplied by the number of classes.

From the point of view of hardware acceleration, trees can be evaluated sequentially or in parallel with an additional sum of output values. The sequential nature of GB does not prevent parallelization of the calculation.

Figure 2: Modified decision tree, processing method using Gradient Boosting technique.

Figure 2: Modified decision tree, processing method using Gradient Boosting technique.

The parameters of real models for classifying encrypted traffic, for example for the QUIC and TLS protocols, are summarized in Table 1. The number of trees is in the order of units of thousands, each tree has an average of less than 500 nodes with a depth of 4 to 57. The internal nodes contain several hundred thousand conditions, many of which are repeated.

| Metrics | QUIC | TLS |

|---|---|---|

| Features | 133 | 107 |

| Classes | 101 | 186 |

| Iterations | 20 | 20 |

| Trees | 2020 | 3720 |

| Tree Depth (Min / Avg / Max) | 4 / 24 / 57 | 4 / 21 / 45 |

| No. of Nodes (Min / Avg / Max) | 9 / 488 / 639 | 7 / 468 / 639 |

| No. of Thresholds (sum / exceptions) | 492345 / 22048 | 868762 / 14978 |

Table 1: Parameters of the created models for classifying QUIC and TLS traffic.

Existing approaches for accelerating decision trees

Hardware acceleration of decision trees has been investigated in several studies 4 5 6. The main approaches include comparator-based architecture (CmpC) and memory-based architecture (MemC).

-

The CmpC architecture first evaluates all conditions in the internal nodes of the tree and inserts the comparison results (0 or 1) into the tree, thereby identifying the leaf node. This approach is simple and powerful, but requires a lot of computing resources and has limited reconfiguration.

-

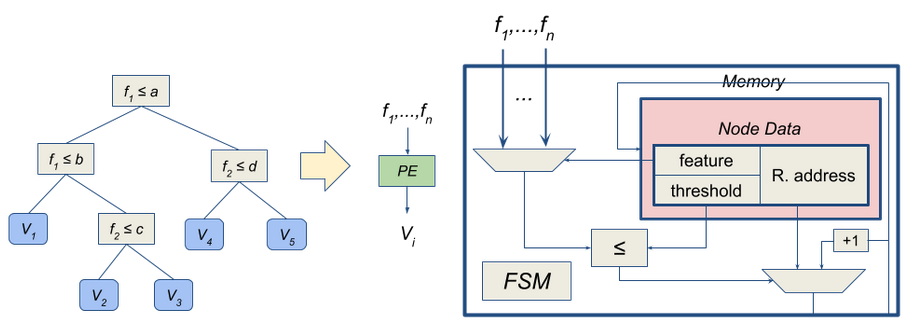

The MemC architecture processes the decision tree from root to leaves according to instructions stored in the instruction memory (see Figure 3). The Processing Element (PE) contains the instruction memory, multiplexers for feature selection and the address of the next instruction, and a comparator. This approach is more computationally efficient and allows for easy reconfiguration of the tree by updating the instruction memory.

Figure 3: Converting a decision tree to a MemC architecture.

Figure 3: Converting a decision tree to a MemC architecture.

We chose the MemC architecture to implement LGBM models on hardware because it scales system performance better and allows processing multiple trees with one PE or one tree with multiple PEs. In addition, it is suitable for eventual tree reconfiguration.

Implementation

We have developed software that automatically converts any LGBM model into a description of a digital circuit in the VHDL language. The inputs are the LGBM model and a configuration file defining the method of quantization of features and output values. The output is a set of VHDL codes implementing the specified model at the hardware level.

The software also generates files for simulation of VHDL codes in the ModelSIM environment, including a testbench file and a set of random test vectors with reference outputs. The user can run the simulation and verify the compliance of the results with the LGBM model at the software level. Furthermore, scripts are generated for the synthesis of VHDL codes for FPGA chips from Intel and AMD manufacturers, compatible with the Quartus and Vivado development environments.

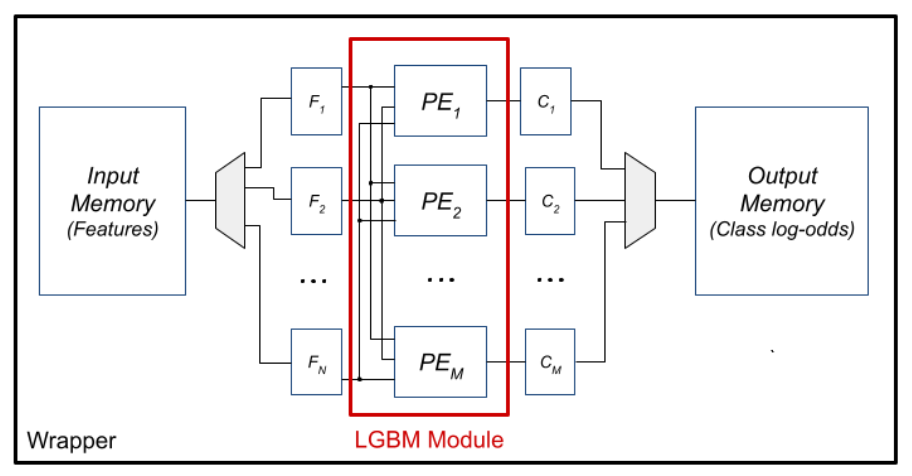

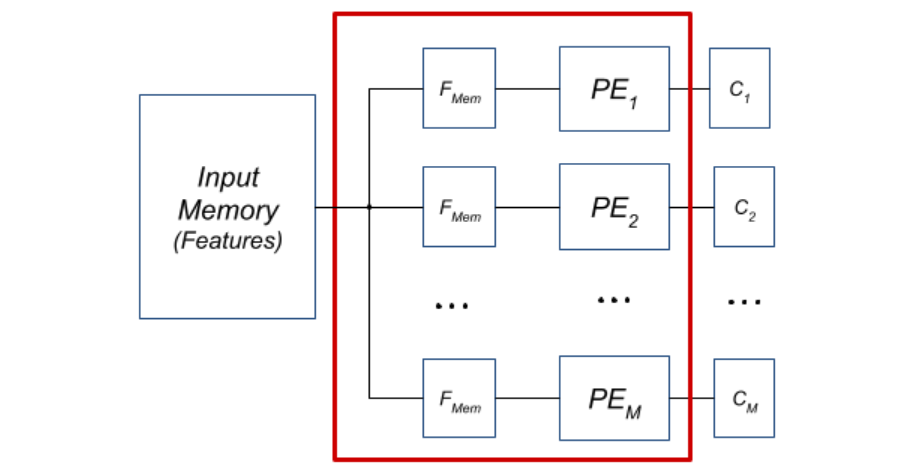

The block diagram of the architecture in the VHDL language is shown in Figure 4. The input features of the tested object are stored in memory (Input Memory), from where they are transferred to registers and fed to the inputs of the process elements via the Wrapper component.

Figure 4: Block diagram of the generated architecture in VHDL.

Figure 4: Block diagram of the generated architecture in VHDL.

In the current version, each processing element processes all trees corresponding to iterations of one class. Thus, the architecture contains as many PEs as there are classification classes, and each PE processes as many trees as were used in the Gradient Boosting iterations (e.g. 20 for the QUIC and TLS models). After processing all iterations, the PE passes the sum of the output values (log-odds ratio) to the Wrapper component, which stores them in the output memory (Output Memory) for further processing or sending to the software.

The software for converting the LGBM model to VHDL was written in Python 3.9 using the LightGBM libraries for working with models and Fxp for converting decimal numbers to fixed point. The core of the software is an algorithm that traverses the decision trees of the input LGBM model and generates the contents of the instruction memory for individual PEs. The list of instructions and configuration parameters is then inserted into pre-prepared VHDL templates.

Experimental evaluation and optimization design

We used the proposed software to accelerate the encrypted traffic classification models at the QUIC and TLS protocol levels. The basic parameters of these models are summarized in Table 1. We synthesized the resulting VHDL code for the Intel Agilex 7 AGFB014 FPGA, which is mounted on the Silicom N6010 network card. The synthesis results are presented in Table 2 (QUIC model) and Table 3 (TLS model).

In the basic implementation, the largest share of memory resource consumption is occupied by M20K (39% for QUIC, 68% for TLS), which serves as instruction memory for process elements (PE). This memory contains a description of the decision trees of a given classification class. Memory requirements increase with the number of iterations and the depth of the trees. To reduce them, we proposed two optimizations that reduce not only memory consumption, but also logical blocks. First optimization: replacing thresholds with their order

During our analysis, we found that identical threshold values are often repeated in trees. For example, the model for TLS contains 868762 internal nodes, but only 14978 unique thresholds. This means that many nodes compare a feature with the same value. If instead of the entire threshold value (e.g., a 32-bit number) we store only its order among unique thresholds (e.g., a 14-bit index), we can significantly reduce the amount of data.

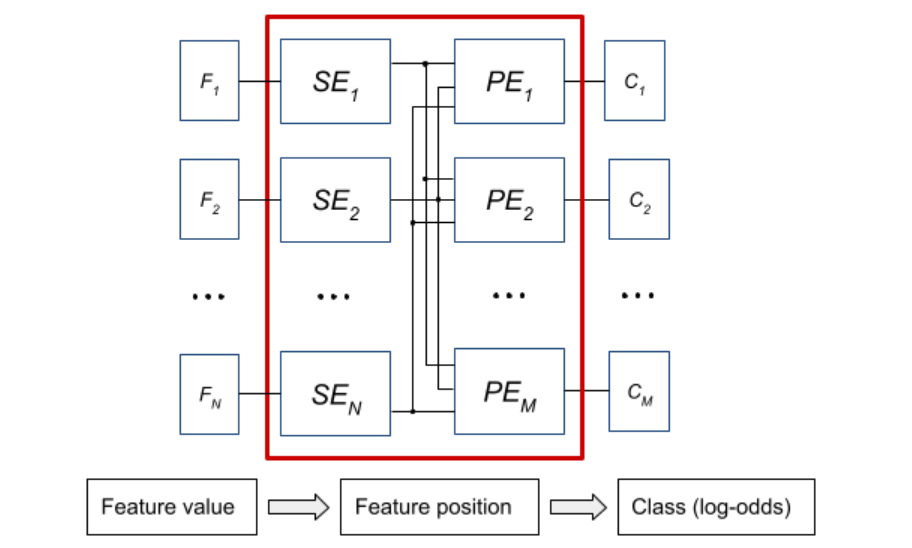

This technique involves:

- replacing the threshold value with its order in a sorted list,

- converting the input features to an order using a Search Engine (SE) block with binary search,

- modifying the PE instruction memory to operate on an index instead of a value.

The resulting architecture (see Figure 5) includes an Input Memory, a Wrapper register for input features, an SE block, and a PE that operates on the order.

Figure 5: Block diagram of the architecture after converting threshold values and input features to positions.

Figure 5: Block diagram of the architecture after converting threshold values and input features to positions.

This optimization brought the following advantages:

- reduction of the width of the multiplexers selecting the input features,

- reduction of the logic (ALM) and memory (M20K) consumption,

- preservation of the same model output as in the non-optimized version.

The synthetic results of this version are presented in the MemC-O column in Tables 2 and 3.

Second optimization: replacement of multiplexers with memories

Each PE must have access to all input features, which in the original architecture was ensured by a large multiplexer. For example, for the TLS model, multiplexers accounted for 87.6% (448 out of 511) of all ALUTs, for QUIC 96.4%. Given their dominance, we designed a new architecture with an FMem block, which copies features from the global memory to a smaller, local memory inside the PE before the actual classification.

Advantages of this optimization:

- significant reduction of logic resource consumption (ALM, ALUT),

- reduction of delay caused by multiplexers,

- preservation of accessibility of all features.

The PE architecture with FMem block is shown in Figure 6. By combining this optimization with the previous one (conversion to order), we achieved a synergistic effect. Logic and memory consumption decreased even more significantly than with individual optimizations.

Figure 6: Block diagram of the architecture after replacing the input feature multiplexers with a set of local memories.

Figure 6: Block diagram of the architecture after replacing the input feature multiplexers with a set of local memories.

The results for the variants with FMem are in the columns MemC-M (only FMem) and MemC-OM (combination of both optimizations) in Tables 2 and 3. Performance and achieved frequencies

| Architecture | ALM | FF | M20K | Fmax [MHz] | Performance [Mcls/s] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MemC | 89 548 (18%) | 28 529 | 2 747 (39%) | 272 | 1,12 |

| MemC-O | 45 034 (9%) | 22 990 | 1 523 (21%) | 301 | 1,24 |

| MemC-M | 19 483 (4%) | 22 554 | 2 836 (40%) | 384 | 1,58 |

| MemC-OM | 32 963 (7%) | 23 768 | 1 457 (20%) | 394 | 1,62 |

Table 2: Synthesis results for the LGBM QUIC model.

| Architecture | ALM | FF | M20K | Fmax [MHz] | Performance [cls/s] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MemC | 101 526 (21%) | 50 710 | 4 837 (68%) | 218 | 1,03 |

| MemC-O | 63 435 (13%) | 37 290 | 2 639 (37%) | 274 | 1,30 |

| MemC-M | 34 928 (7,2%) | 41 125 | 4 917 (69%) | 362 | 1,72 |

| MemC-OM | 55 667 (11%) | 38 044 | 2 539 (36%) | 392 | 1,86 |

Table 3: Synthesis results for the LGBM TLS model.

The optimizations also had a positive effect on the achievable operating frequency (Fmax). The MemC-M variant increased the frequency by more than 100 MHz compared to the basic implementation. Higher frequency directly increases the number of classifications per second, as processing each vector takes a constant number of cycles, given by the number of model iterations. Compared to the original implementation at the software level, which achieves performance in the order of units to tens of thousands of classifications per second, the hardware achieves acceleration in the order of hundreds to thousands.

Summary and tool availability

We have designed and implemented an open-source tool for converting LightGBM models to digital architecture in VHDL. The tool generates:

- VHDL code for FPGA (Intel Quartus, AMD Vivado),

- test vectors and testbench for ModelSim,

- simulations to verify compliance with the original model.

Thanks to optimization support, output architectures can be easily synthesized even for larger models, while the resulting consumption of FPGA resources is significantly lower. The resulting solutions can be deployed in environments where high classification speed is required - typically on operational data collectors from multiple probes.

The tool is available on GitHub: https://github.com/CESNET/lgbm2vhdl

This work was also published at the FCCM 2024 conference:

T. Martinek, J. Korenek and T. Cejka, “LGBM2VHDL: Mapping of LightGBM Models to FPGA,” in 2024 IEEE 32nd Annual International Symposium on Field-Programmable Custom Computing Machines (FCCM), Orlando, FL, USA, 2024, pp. 97-103, doi: 10.1109/FCCM60383.2024.00020.

References

-

LUXEMBURK Jan, HYNEK Karel, and ČEJKA Tomáš. Encrypted traffic classification: the QUIC case. In: 2023 7th Network Traffic Measurement and Analysis Conference (TMA), Naples, Italy, 2023, pp. 1-10. ↩ ↩2

-

KE Guolin, MENG Qi, FINLEY Thomas, WANG Taifeng, CHEN Wei, MA Weidong, YE Qiwei, and LIU Tie-Yan. LightGBM: a highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’17). Curran Associates Inc., Red Hook, NY, USA. 2017, pp. 3149–3157. ↩

-

LUXEMBURK Jan and ČEJKA Tomáš. Fine-grained TLS Services Classification with Reject Option. In: Elsevier Computer Networks journal, vol. 220, 2022. DOI: 10.1016/j.comnet.2022.109467. ↩

-

STRUHARIK J. R.. Implementing decision trees in hardware. In: 2011 IEEE 9th International Symposium on Intelligent Systems and Informatics. Subotica, Serbia, 2011, pp. 41-46. DOI: 10.1109/SISY.2011.6034358. ↩

-

VAN ESSEN B., MACARAEG C., GOKHALE M., and PRENGER R. Accelerating a Random Forest Classifier: Multi-Core, GP-GPU, or FPGA? In: 2012 IEEE 20th International Symposium on Field-Programmable Custom Computing Machines. Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012, pp. 232-239. DOI: 10.1109/FCCM.2012.47. ↩

-

ALCOLEA A.; RESANO J. FPGA Accelerator for Gradient Boosting Decision Trees. Electronics 2021, 10, 314. DOI: 10.3390/electronics10030314. ↩